Make a donation to the Museum

World Peace Through World Trade

In 1939, when Europe was on the brink of another world war, a group of business and trade associations created the first World Trade Center dedicated to promoting world peace through world trade. Though just a temporary pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, the idea of a neutral location where world business leaders could come together to exchange ideas and products resulted in a permanent World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

The First World Trade Center

The first World Trade Center was conceived as a pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, New York. Sponsored by a group of business and trade associations, the pavilion hosted an exhibition dedicated to the concept of “world peace through world trade” and served as the headquarters for visiting trade groups and students to the fair. The pavilion was temporary, but the idea of a permanent World Trade Center lived on and was revived in the late 1950s.

Aerial photograph of lower Manhattan in 1954. Courtesy of United States Geological Survey.

Revitalizing Lower Manhattan

Through the 1940s, lower Manhattan held its status as the nation’s largest central business district. But in the 50s and 60s, many corporations relocated their headquarters more than 60 blocks north to the modern glass towers on Park Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas. Stymied by its irregular jumble of narrow streets, congestion, and an increasingly obsolete, decaying waterfront, downtown was being eclipsed by midtown. Furthermore, as container shipping increased, Manhattan’s ports lacked adequate docking depth and the space to build what was needed to accommodate these large and heavy freight transport vessels, sending maritime traffic to New Jersey’s deeper receiving areas. Witnessing this exodus, vice president of Chase Manhattan Bank, David Rockefeller, founded the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (D-LMA) in 1958. The D-LMA sought to bring together leaders in the business community to foster and promote the economic, civic, social, and cultural welfare of lower Manhattan.

Shortly after its establishment, the D-LMA commissioned architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) to develop a plan for a 13.5-acre lower Manhattan site that would include a 70-story hotel and office building, an international trade mart and exhibition hall, and a central securities building. Rockefeller viewed the proposed international trade mart, or World Trade Center, as the centerpiece of the plan. He believed a World Trade Center would stimulate international business development and act as a symbol of the United States’ expanding leadership in the international business community.

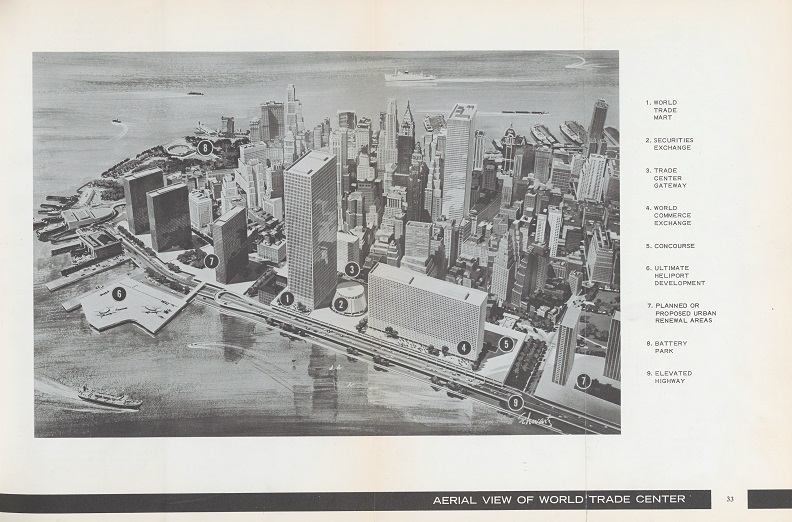

Rendering of the proposed World Trade Center on the east side of lower Manhattan. Courtesy of the General Research Division, The New York Public Library, 1961.

The original site proposed for redevelopment lay along the East River, between Old Slip and Fulton Street. But when the Port Authority, an interstate agency that manages the bridges, tunnels, marine ports, and airports of New Jersey and New York, was charged with planning and building the complex, the site was moved to the west side of lower Manhattan to strengthen ties between the two states.

A sign for the future site of the World Trade Center posted on West Street between Dey and Cortlandt Streets, December 1966. Collection 9/11 Memorial Museum, Gift of George V. V. Rouse.

Casualties of Progress

In 1962, the states of New York and New Jersey authorized the Port Authority to develop a World Trade Center on the west side of lower Manhattan. The chosen site, which ran south from Vesey Street to Liberty Street and west from Church Street to West Street, was situated in the heart of a business district known as Radio Row. Earning its nickname from its concentration of small businesses specializing in radios and electronics, Radio Row was home to more than 300 businesses and 30,000 employees during its heyday. The Port Authority, however, faced opposition from local business owners who protested and refused to move, sparking a legal battle. Ultimately, in November 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the merchants’ appeal against the Port Authority. Through eminent domain, a law empowering the government to seize land for public use, evictions proceeded and Radio Row was razed to create the 16-acre superblock designated for the World Trade Center.

10 Million Square Feet of Office Space

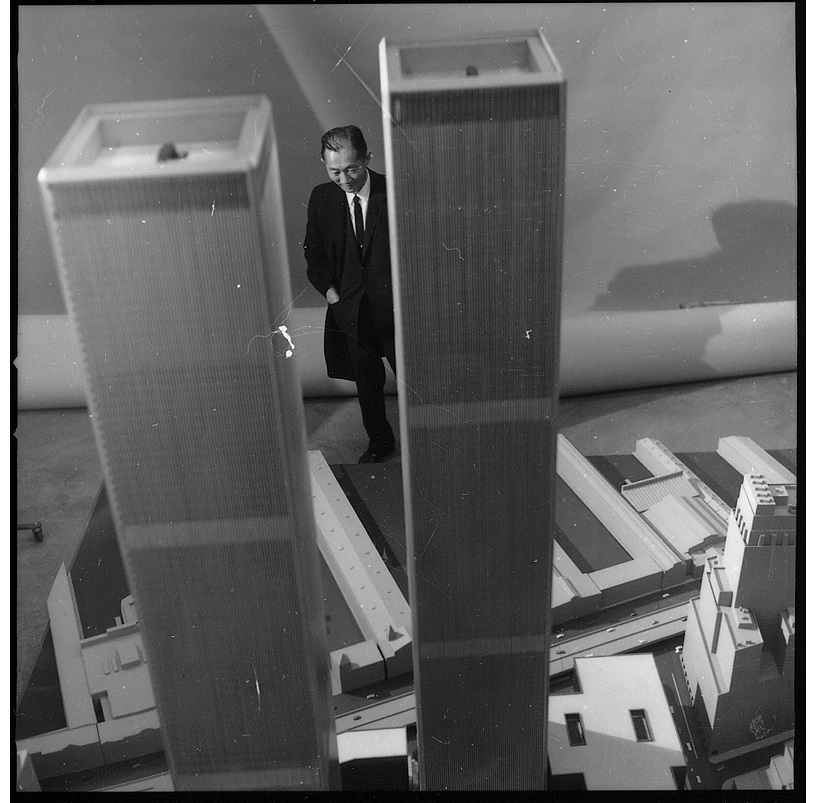

By 1964, when the final design of the World Trade Center was unveiled to the public, the original scope of the complex had grown from a single 70-story tower with several smaller buildings to two 110-story towers flanked by four smaller structures. In the 1980s, a seventh building would be added to the complex, just north of the plaza. The final design, proposed in 1964, was conceived by Detroit-based architect Minoru Yamasaki and accommodated almost 10 million square feet of office space.

Minoru Yamasaki standing beside a model of the World Trade Center, circa 1970. Photograph by Balthazar Korab, Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Balthazar Korab Collection.

“The World Trade Center is a living symbol of man’s dedication to world peace . . . a representation of man’s belief in humanity, his need for individual dignity, his beliefs in the cooperation of men, and through cooperation, his ability to find greatness.” —Minoru Yamasaki, Chief Architect of the World Trade Center, remarks at opening ceremonies and dedication April 4, 1973

Through the collaboration of Minoru Yamasaki & Associates and New York City–based architects Emory Roth & Sons, the Twin Towers began their vertical climb in 1968. With the topping off of the North Tower in December 1970 and the South Tower in July 1971, the World Trade Center complex was dedicated in 1973.

Aerial photograph of lower Manhattan, undated. Collection 9/11 Memorial Museum, Gift of Keystone Aerial Surveys, Inc.

Ideals in Action

The World Trade Center welcomed its first tenants in 1970. They included exporters, importers, freight forwarders, Custom House brokers, international banks, trade associations, United States and foreign government trade agencies, state government trade representatives, and other international trade organizations. Despite the significant number of federal, state, and city agencies that occupied the World Trade Center, the number of companies leasing office space in the towers remained low throughout the 70s and early 80s, but when New York City’s economy boomed in the 1990s and the city needed more office space, the Twin Towers filled with tenants.

By the late 1990s, a new global culture had emerged linking the economic fortunes of distant nations and prompting a new wave of immigration around the world. Nowhere was this transformation more apparent than at the World Trade Center where financial transactions occurred 24 hours a day and a diverse working population streamed in and out of the buildings. Within a short period of time at the end of the 20th century, the forces of globalization had made the towers the most familiar structures on the most familiar skyline in the world.

For much of the world, globalization in the 1990s provided opportunities for the exchange of goods and ideas. In some parts of the Middle East, however, this decade of globalization was perceived as an incursion of Western influence, particularly American influence, in Muslim-majority countries. For Islamist extremists like al-Qaeda, America’s presence in the Middle East was perceived to be a threat to the religious beliefs and values of the Islamic world. In 1996, al-Qaeda’s founder and leader, Osama bin Laden, declared a jihad, a religiously-sanctioned war, against the United States. He believed a combination of economic and military attacks would convince the U.S. to withdraw from the Middle East, and where better to deal this devasting blow on U.S. soil than the World Trade Center, the ultimate emblem of American economic and global power.