Make a donation to the Museum

Shaping Lower Manhattan’s Skyline

The Twin Towers were designed to be the tallest buildings in the world. Their soaring height made them a symbol of American grandiosity but also made them vulnerable to aerial attack. Due to the ingenuity of architects and engineers in the 1960s who explored new construction methods to build the 110-story towers, the Twin Towers climbed above lower Manhattan’s existing skyline and loomed over New York City.

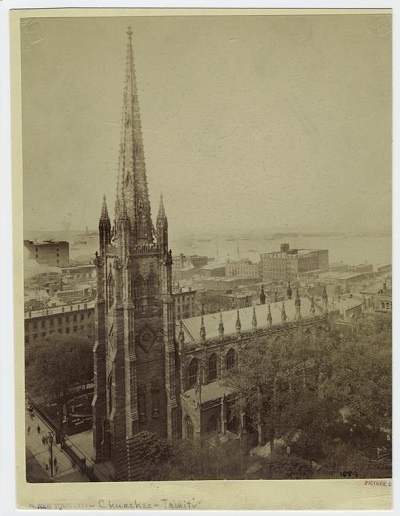

Trinity Church, New York City, photographed from the roof of the Equitable Building, circa 1889. Courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

Technological innovations in building construction over roughly the last 150 years in America have transformed lower Manhattan’s skyline. Before the introduction of iron, and later steel, frame construction in the late 19th century, building skyscrapers in New York City was neither profitable nor practical. Thick masonry walls on lower floors were required to build taller buildings, which reduced the amount of rentable space inside the building. In 1846, the tallest structure in Manhattan was Trinity Church, a 281-foot brownstone building in lower Manhattan with load-bearing walls. It was surpassed in 1890 by the now razed World Building, a steel construction building which topped the church at 309 feet. But within just two decades, the height of New York City’s tallest building would more than double to 700 feet with the completion of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower in 1909. Manhattan’s office buildings continued to grow higher through the 20th century. The literal highpoint of 1,368 feet was reached in 1970 with the completion of the North Tower of the World Trade Center (also known as the 1 World Trade Center), the first of the Twin Towers to be finished.

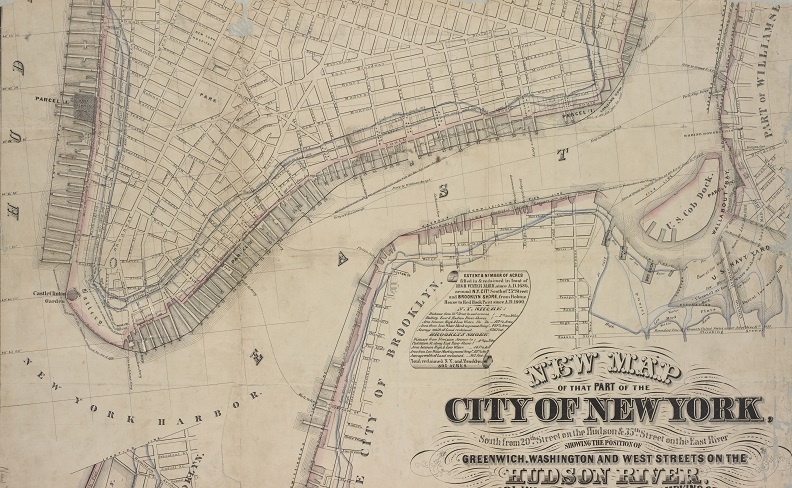

Map of lower Manhattan showing the natural shorelines of the City of New York since 1686. Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library, 1862.

A Changing Shoreline

As lower Manhattan rose upward, it also grew outward. When the first Dutch colonists settled on the southern tip of Manhattan Island and founded New Amsterdam in 1626, they soon found themselves without enough land to support their growing settlement. Bounded by a wall on the north—a boundary line that we now call Wall Street—the Dutch looked to the shoreline for expansion. Colonists began “reclaiming” land by dumping city debris such as dirt and garbage into the rivers, extending the streets 200 to 400 feet out between 1680 and 1731. At the beginning of the 19th century, the island expanded again, moving the natural shoreline from Greenwich Street to present-day West Street on the west side of lower Manhattan. The landfill created and utilized during this period of land reclamation is what the western portion of the original World Trade Center complex was built upon.

Building on Unstable Ground

When planning commenced for the construction of the World Trade Center, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had to find a way to build the two largest skyscrapers in the world on landfill. This unstable ground meant that engineers would need to dig down to a layer of Manhattan schist, the strong and durable bedrock that formed 450 million years ago, to anchor the foundation of the Twin Towers. But even before digging could begin, engineers had to figure out how to create a waterproof barrier between the Hudson River and the site to prevent water from seeping through the soil and flooding the hole during construction. The solution would come all the way from Italy with a new underground and deep foundation construction technology used a few times in America but never before at the scale of the World Trade Center.

Aerial view of the World Trade Center site being actively excavated in 1968 with the north and west sides of the slurry wall visible. Collection 9/11 Memorial Museum, Gift of George V. V. Rouse.

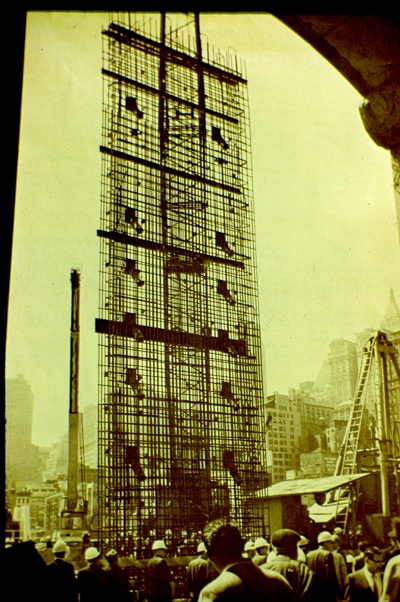

Photograph of a reinforcing steel cage being lowered into a trench to construct a portion of the slurry wall in 1967. Collection 9/11 Memorial Museum, Gift of Arturo L. Ressi di Cervia.

The Slurry Wall

The slurry wall method was patented in Italy in the late 1940s by the ICOS Company and first used during the construction of Milan’s subway system in the 1950s. The technique required the excavation of a trench, filling the trench with a mixture of clay and water known as slurry, and casting a steel-reinforced concrete wall within the trench. At the World Trade Center site, this was done in stages, one panel at a time, each measuring approximately three feet thick, 22 feet wide, and between 70 to 80 feet tall. The completed slurry wall consisted of 158 panels, enclosed 11 of the 16 acres of the World Trade Center site, and measured 3,500 feet long.

After the wall was complete, crews excavated the earth within the perimeter to reach the Manhattan schist and anchor the foundation of the Twin Towers to the bedrock. The World Trade Center’s basement floors were installed next, which provided permanent lateral support for the slurry wall. The resulting cavity beneath the World Trade Center became affectionately known as the bathtub—a counterintuitive description since its essential purpose was to keep water out. The technique was integral to the construction of the Twin Towers.

On the Staten Island Ferry, looking back toward the skyline of lower Manhattan, 1973. Photograph by Wil Blanche, Courtesy of the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Archives.

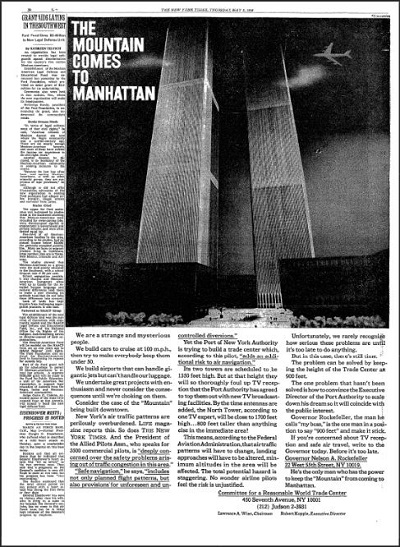

Advertisement in the New York Times on May 2, 1968. Courtesy of Peter L. Malkin and Malkin Holdings LLC.

The World Trade Center’s place in New York City’s skyline earned it iconic landmark status throughout its lifetime. Featured in movies, television shows, commercials, and other media, the Twin Towers’ silhouette was recognizable throughout the world. But constructing and operating some of the largest and most symbolic facilities in the world came with unforeseen consequences. An advertisement paid for by the Committee for a Reasonable World Trade Center and printed in the New York Times on May 2, 1968, warned of the risk the towers’ height posed to air navigation. The advertisement’s artwork, shown in the image to the left, depicts an airplane flying precariously close to the top of the North Tower. Though the Committee points out the hazard of having to change flight patterns and minimum altitudes to accommodate these new aerial obstacles, no one ever imagined a scenario where airliners would be intentionally crashed into the towers. This “failure of imagination” as later described by the 9/11 Commission that was set up to investigate the circumstances surrounding the attacks, included our inability to look beyond our aspirations of building tall and see the towers’ vulnerability.